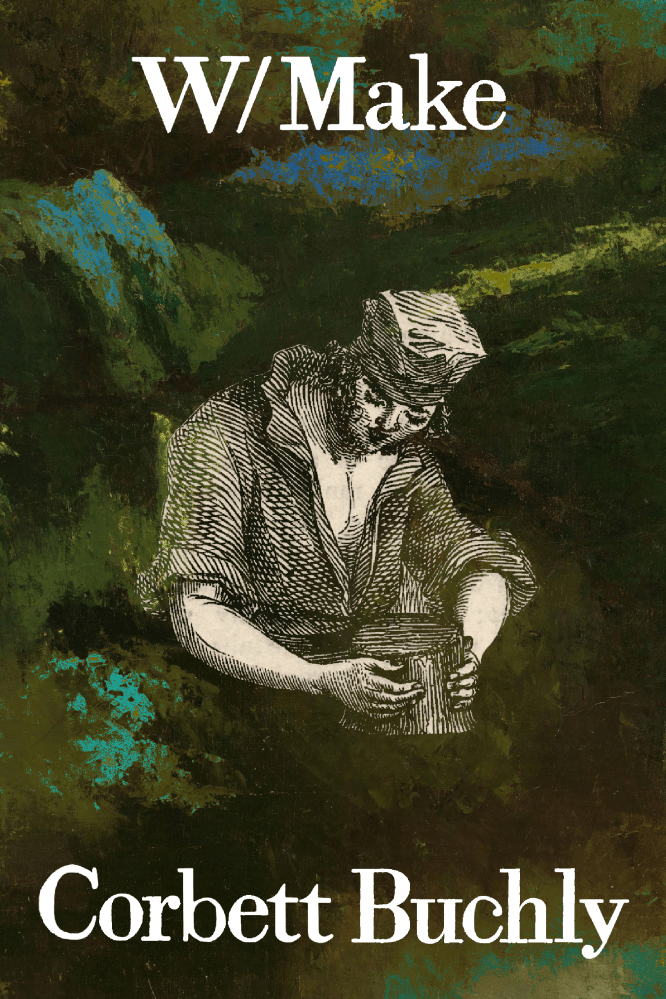

It’s finally here! My first collection of poems are now out in book form by Bottlecap Press!

Buy it here: https://bottlecap.press/products/wmakcb

This poetry chapbook represents the first snapshot behind years of intense focus of writing and publishing poetry. It was important to me that I followed a traditional path to publication. And here we are!

If you are a maker of things, whether that be writing or drawing or crafting or woodworking or cooking, if you find time for creative expression, I believe this book will resonate with you. In W/Make, I dive into the different ways we have making art and of how we think as makers. There are also a few poems that hint at my beginnings as an artist. I was writing stories from a young age, not knowing at that time that it was not something everyone did. But it was in high school, thanks to a terrific English teacher, Connie Nokes (now Connie Morris), that the world of literature really opened up for me. And for that I am eternally grateful. I write poetry for one primary reason. I absolutely love it. I know there’s no money in it. But it’s my passion.

In this chapbook, you’ll find the mysterious:

“only after descending/past the usual depths…did the scientists discover us/on a shelf miles into the trench”

You’ll find the sentimental:

“child in snug lean/against a mother’s ribs/the book splayed before us.”

You’ll find the humorous too:

“when did they first replace the processed snacks/in the break room vending machine with poems.”

I’m anxious to hear how you like the poems. Let me know in the comments or email me at corbettbuchly@gmail.com

Please note: This book will not be available on Amazon. To get it, you’ll have to order from Bottlecap Press, or if you’re in the neighborhood, from me.